Bridging the Gap between Mental Health and the Disaster Cycle

Written by Angela Hogg, MSW

Michael Ross, MSW, LCSW

Michael Ross, MSW, LCSW is a trauma-informed mental health professional who has spent the early part of his career fighting for parity and working with complex psychological trauma. What becomes obvious after speaking with Mr. Ross is that he is incredibly passionate about mental health and the reduction of psychological suffering. His academic background is as eclectic as his professional efforts. A former photographer and cinematographer, Michael made his way into mental health out of a desire to understand his own experiences with trauma, depression, and a traumatic brain injury. His journey towards becoming a national voice in disaster mental health and resilience began by returning to college to pursue a Bachelor of Arts in Religious Studies, with a focus in esotericism and eastern thought. This degree led Michael to reconnect with his interest in psychology and trauma. Michael then completed a Master of Social Work in Mental Health and Addiction; where he focused on Veteran’s mental health. Which, in turn, led Michael to complete a graduate certificate in Homeland Security and Emergency Management with a focus in disaster resilience.

During Michael’s studies, he kept coming back to the importance and power of psychological trauma. This led him to focus on a clinical framework for reducing the psychological impact of traumatic events and, as a result, the quantification of trauma and toxic stress. This led him to the work of Dr. Merritt Schreiber and the only known real-time evidence-based rapid mental health triage strategy and system, PsySTART.

As a clinician, Michael has spent his early career focusing on helping individuals and groups develop cognitive resilience and psychological resistance to trauma, disasters, and biologically toxic levels of stress. Trained in a number of clinical approaches, Ross has direct experience working with clients struggling with co-occurring disorders, serious and pervasive mental illness, toxic stress, and trauma. He has worked in inpatient and outpatient settings, where he was responsible for individual, group, and family treatment in a time delineated environment.

In addition, Michael teaches courses for the Indiana University School of Social Work and is currently working with faculty to develop research opportunities and provide practicum supervision for students interested in macro level social work.

Michael Ross is also a former MESH Coalition innovator. While at the MESH Coalition, Ross was the Senior Crisis and Continuity Advisor for Behavioral Healthcare and Resilience. In this role, he was tasked with integrating mental health into the healthcare coalition as equal-level stakeholders. The core of this work focused on teaching about disaster resilience; introducing trauma informed care to homeland security and emergency management; teaching about psychological trauma in relation to disasters and terrorism; and advocating for national and international paradigm shifts intended to create resilience rated-citizens and cities capable of responding to crisis and toxic stress. Before leaving MESH, Mr. Ross co-designed and co-authored a National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) grant for bed tracking that focused on increasing access to care for individuals struggling with substance abuse and dependence.

If you ask Michael what the future of disaster mental health and addiction looks like he will tell you, “It must be a modular and scalable system based on a crisis triage to care continuum that uses the work of Dr. Merritt Schreiber as its spine.” In addition, Michael would not hesitate to tell you, “The work must focus on pre-event resilience enhancement and more effective integration of mental health, addiction treatment, and trauma-informed care in the disaster cycle through PsySTART. Ultimately, providing a system that is focused on mitigating the impact of toxic stress and enhancing disaster resilience, resistance, and recovery.”

The process of building resilient communities may take a high level of creativity and collaboration from all stakeholders involved, and is necessary before, during, and after a disaster. Research suggests that the degree and rate of resilience in the aftermath of a disaster depends on the combination of risk factors and distress level prior to the disaster[1]. If applications and collaboration can provide appropriate supports to affected individuals and communities, then the opportunity exists to improve resilience and the recovery process. This trajectory promotes a concept of the World Health Organization, “building back better,” and improves the community’s resilience when encountering future disasters.

“Behavioral health is an integral part of the public health and medical response to disaster or public health emergency, and should be fully integrated into preparedness, response, and recovery activities.”

- Health and Human Services, 2014

Michael’s mission is to enhance the resilience of those living in the state of Indiana. In order to realize this goal he has worked with experts in the field to develop an approach to building community resilience before, during, and after disasters that is five-fold:

1. Effective systems to triage—particularly, risk exposure to reduce further exacerbation of distress.

2. Ensure adequate systems are in place to smoothly scale-up when necessary.

3. Provide, coordinate, and link effected individuals, communities, and systems with access to supportive resources (i.e. natural supports, psychological first aid, mental health treatment, at-large assistance such as 211).

4. Promote trauma-informed response systems that are resilient with well-defined self-care plans (i.e. Anticipate Plan Deter).

5. Identify, partner, and fund integrative interventions for long-lasting capacity building at the community level (i.e. addressing social determinants of health, promoting access to care, reducing stigma, and building social capital).

More frequently than ever before, communities are faced with responding to the consequences of disasters—including mass violence, major incidents, and climate change—and subsequent trauma that reverberates through the community. Those who are affected not only include direct victims, but also first responders. Additionally, individuals, families, communities, and society can experience distress through learning of an event[2]. Particularly concerning, is that vulnerable populations are disproportionately at risk in disasters.

According to the National Research Council policy directive the goal of disaster preparedness is to generate resilience, not to generate short-term solutions[3]. The focus of this goal then should be the use cutting-edge technologies, evidence-based protocols, and the National Incident Management System (NIMS) in order to develop a framework for care providers to function efficiently and effectively[4]. As a result, local communities have a unique opportunity to leverage evidence-based skills and knowledge in an interdisciplinary environment in order to generate socially just strategies for creating citizens and cities that are more resilient and capable of returning to homeostasis after a traumatic event or disaster.

Ultimately, the goal of building community level resilience involves providing tools and aiming to enhance protective factors and systems. This is where PsySTART comes in.

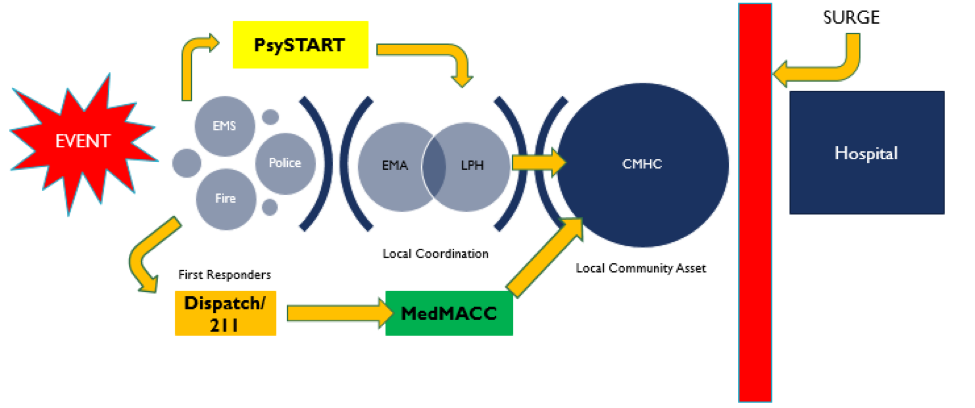

PsySTART—developed by Dr. Merritt Schreiber—is the only known evidence-based rapid mental health triage strategy and system. This system is used during an emergency to rapidly assess individuals for exposure to toxic stressors and traumatic events, and match them with support services if needed. The PsySTART is intended to enhance real-time decision making by creating a common operating picture of the psychological footprint of an event. The tool can be used by medical professionals, mental health professionals, first responders, and trained non-professional volunteers alike. The system has been used after the Boston Bombing, the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, Sandy Hook shooting, Hurricane Harvey, Superstorm Sandy, Typhoon Haiyan, as well as in Tennessee, Texas, Washington D.C., Los Angeles County hospital in California, and Seattle.

Gathering information on the status of an individual addresses the problem of mental health surge and effective resource allocation by ensuring needs of the impacted population are appropriately addressed and prioritized. In addition, PsySTART creates a new system for linking those affected with timely supports and appropriate evidence-based care. Furthermore, the tool facilitates the identification of individuals that would benefit from secondary mental health assessment, limited crisis intervention and/or evidence-based mental health services by a trained mental health professional; particularly when specialized staff is limited[5].

Critically, PsySTART supports healthcare and emergency workers in efforts to adequately determine and triage the most pressing needs and refer impacted individuals to appropriate levels of mental health resources at the time of need. Individual results taken are aggregated to provide a real-time picture of how a disaster or extreme stressors are affecting a community or geographical area.

Implementation of PsySTART provides a route for agencies at the local, county, state, and federal levels to monitor and identify specific geographic areas of increasing need by using real-time data. Descriptions of additions that PsySTART adds for each level of response are listed in Figure 1. The systems that have begun implementation have made data available at all levels to identify concerns and provide strategies to support resilience efforts before, during, and after events.

PsySTART allows for clear collaboration between the community’s needs and first responders to appropriate resource allocation. This offers specialized data to be used in the disaster event for justification of requesting additional resources. Most importantly, this promotes improved ability for communities to bounce back and become stronger after experiencing the event by ensuring resources are available for those who were identified to have been exposed to elevated levels of risk.

Enhancing resilience requires building a more integrated system to maximize the collaboration between agencies, especially prior to the event. This effort includes effectively and comprehensively collaborating with mental health centers, public health agencies, first responders, hospitals, and local organizations and affiliated agencies to coordinate community needs. Coordination among providers is key to ensure continuity among existing health systems and during the time when resources scale up[7][8]. Collaboration across varied professions and organizations requires all parties to be present at the table throughout the disaster cycle, and requires an acknowledgement that disaster mental health is critically important to the resilience of individuals, communities, and organizations.

The proposed framework to enhance long-term resilience before, during, and after disaster events has begun implementation. This task requires a high level of creativity and partnership from stakeholders. At this time, the need exists to improve collaboration at all levels, address social determinants of health, build social capital, and ensure the responder workforce is equipped and prepared prior to a highly stressful event. By addressing trauma exposure early, opportunities exist to improve the recovery process and enhance resilience for Hoosiers most vulnerable to the effects of trauma.

A multitude of variables determine how human beings respond to stress and trauma[9]; however, we know that genetics, gender, age, social and cultural environment and developmental exposures to stress influence neurobiological systems and moderate PTSD risk. Factors increasing the risk of developing further psychological distress in the aftermath of a disaster relate to direct exposure and pre-event experience; as well as other complex factors. Risk factors associated with direct exposure include: severity of the disaster; loss of life (i.e. family, friends, pets, community members); heavy damage to property; loss of property; and displacement[10]. In addition, age has been identified as influential risk factor; particularly for children, youth, and the elderly[11]. Additional risk factors include pre-existing mental health diagnosis or substance use[12].

During these complex events, the percentages of individuals that are diagnosed with a serious mental illness increases by 1% (i.e. psychosis, severe depression, and severe disabling anxiety disorder) and mild or moderate mental illness increases by 10%[13]. Studies have shown an increase of 30-40% in rates of new incidences of PTSD and depression among populations directly affected by disasters[14][15]. Additionally, studies have also revealed that rates of domestic violence, sexual assault, and human trafficking often increase after a disaster. It should be noted that longitudinal studies have shown that early identification can mitigate the incidence of long lasting and risk for mental health problems[16][17]. This points to the need to adequately measure risk, exposure, and acute distress.

Untreated trauma can lead to changes in behavior and mental health, as well as symptoms in the physical body. The effects of trauma not only are seen in those directly exposed, but also evident in future generations. Intergenerational trauma has been studied in offspring of Holocaust survivors[18], children of women that survived September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks in New York[19], refugee families[20], and Hurricane Katrina survivors[21]. Results of these studies revealed long lasting vulnerabilities including health concerns and psychological distress.

“The stress we undergo either as a result of a single critical incident that had a significant impact upon you, or the accumulation of stress over a period of time. This stress has a strong emotional impact to providers, regardless of their years of service”

– National EMS Management Association (NEMSMA), Mental Health and Stress in Emergency Medical Services, February 21, 2016

Based on the overwhelming interdisciplinary body of research we can see that psychological trauma is a part of life and disasters. It is also important to note that even though everyone experiences trauma differently, the data indicates that most individuals who consume public services are often products of significant and lengthy traumas that can be physical, sexual, emotional, social, or spiritual in nature[22]. These traumas create a deep wounding that can increase rates of chronic stress and reduce resilience. Typically, these individuals will often struggle with chronic stress related issues.

It is important to note that this conception of the psychological power of trauma creates a new paradigm where existing evidence-based approaches for the processing of suffering can be adapted and applied to the disaster cycle in order to continue towards goal of the New Freedom Report on Mental Health; by increasing hope, resilience, and self-direction of individuals impacted by a disaster.

PsySTART Responder – Burnout, compassion fatigue, reduction in morale, and productivity fluctuations are examples of a need to ensure a resilient workforce. Disasters and traumatic also impact responders.

Research has shown that disaster responders have a prevalence of developing PTSD of approximately 10-20%, with differences in rates depending on the level of destruction and causal type[23]. While disaster volunteers have between a 24-46% risk of developing PTSD[24]. Proactively implementing pre-event training on preparation[25], building protective factors[26], implementing a system to assess stress and concerns[27] is necessary to employ across disaster responder and volunteer staff.

Anticipate. Plan. Deter. – APD is a tool used to monitor and enhance overall resilience for responders, mental health providers, and other medical professionals alike. Divided into three steps, APD outlines a strategy for responders to plan ahead, identify how they generally feel when facing stress, consider experiences or situations they may face and how they might react or be affected, and then identify coping strategies and social supports in advance of the event. During or after work shifts, responders can assess and reflect on their exposure to monitor stress, giving them information to utilize their pre-developed plan to cope.

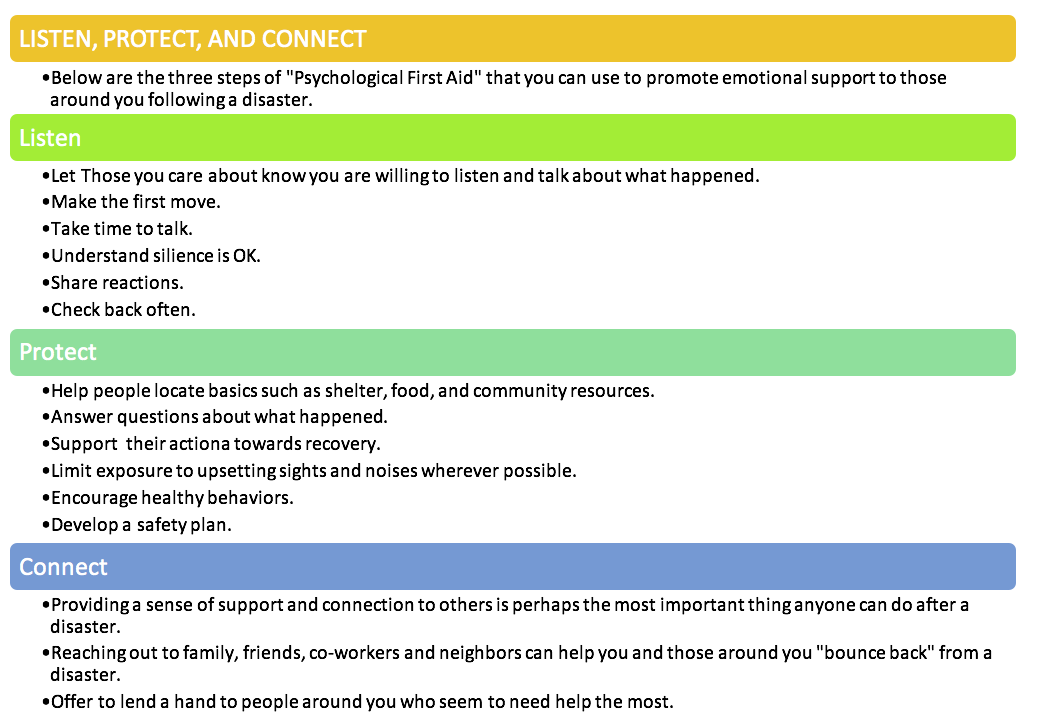

Listen Protect Connect. – LPC is an evidence-informed approach built on the concept of human resilience that details utilizing psychological first aid in the aftermath of a disaster. This system provides step-by-step instructions of specific skills and techniques to reduce further exposure to stress and trauma. Psychological first aid attempts to stabilize psychological functioning, mitigate distress, return to pre-event functioning, and access additional resources if necessary[28]. The skills and techniques can be used by non-professionals (i.e. family, friends, neighbors, coworkers, shelter staff) in a community setting, and is specifically designed to build capacity of neighbors and loved ones to empathetically and strategically support one another. Social supports have been associated with positive growth after the traumatic event, particularly among children[29]. When determined appropriate, those in need of additional support can be linked with community resources. In preparation and in an effort to proactively build resilience in advance of disaster events, LPC could be offered at community centers, schools, or neighborhood meetings.

References

- Norris, Tracy, & Galea, 2009

- Galea, Nandi, Vlahov, 2005; Norris et al., 2002

- National Research Council, 2012

- National Research Council, 2013

- Schreiber et al., 2014

- Schreiber et al., 2014

- Reifels et al., 2013

- WHO, 2013

- Heirm & Nemeroff, 2009

- Frankenberg et al., 2008; van den Berg, Wong, van der Velden, Boshuizen, & Grievink, 2012; Paxson, Fussell, Rhodes, & Waters, 2012

- as cited in IOM, 2015; Henley, Marshall, Vetter, 2011; Phillips, 2009

- Norris et al., 2002; Inter-Agency Standing Committee [IASC], 2007

- IASC, 2007

- Galea et al., 2005

- Neria, Nandi, Galea, 2008

- Holgersen, Klöckner, Jakob Boe, Weisæth, & Holen, 2011

- Schreiber, Yin, Omaish, Borderick, 2014

- Yehuda et al., 2008

- Yehuda et al., 2005

- Sangalang & Vang, 2017

- Goodman & West-Olatunji, 2008

- SAMHSA, 2012

- Galea et al., 2005

- Thormar et al., 2016

- Walsh, 2009

- Reissman et al., 2009

- Sylwanowicz et al., 2017

- Everly & Flynn, 2006

- Kronenberg et al., 2010

Chandra, A., Acosta, J., Stern, S., Uscher-Pines, L., Williams, M. V., Yeung, D., . . . Meredith, L. S. (2011). Building community resilience to disasters: a way forward to enhance national health security. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Health.

Dirkzwager, A. E., Kerssens, J. J., & Yzermans, C. J. (2006). Health Problems in Children and Adolescents Before and After a Man-made Disaster. Journal of The American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(1), 94-103.

Everly, G. J., & Flynn, B. W. (2006). Principles and practical procedures for acute psychological first aid training for personnel without mental health experience. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, 8(2), 93-100.

Frankenberg, E., Friedman, J., Gillespie, T., Ingwersen, N., Pynoos, R., Rifai, L. U., & ... Thomas, D. (2008). Mental Health in Sumatra after the Tsunami. American Journal of Public Health, 98(9), 1671-1677.

Galea, S. (2007, April 24). The long-term health consequences of disasters and mass traumas. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal Supplement. pp. 1293-1294.

Galea, S., Nandi, A., & Vlahov, D. (2005). The epidemiology of post-traumatic stress disorder after disasters. Epidemiologic Reviews, 27, 78-91.

Gunnar, M., & Quevedo, K. (2007). The neurobiology of stress and development. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 145–173. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085605

Heim, C., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2009). Neurobiology of posttraumatic stress disorder. CNS Spectrums, 14(1 Suppl 1), 13–24.

Hamiel, D., Wolmer, L., Spirman, S., & Laor, N. (2013). Comprehensive Child-Oriented Preventive Resilience Program in Israel Based on Lessons Learned from Communities Exposed to War, Terrorism and Disaster. Child & Youth Care Forum, 42(4), 261-274.

Henley, R., Marshall, R., & Vetter, S. (2011). Integrating Mental Health Services into Humanitarian Relief Responses to Social Emergencies, Disasters, and Conflicts: A Case Study. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 38(1), 132-141.

Holgersen, K. H., Klöckner, C. A., Jakob Boe, H., Weisæth, L., & Holen, A. (2011). Disaster survivors in their third decade: Trajectories of initial stress responses and long-term course of mental health. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 24(3), 334-341.

Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. (2015). Healthy, resilient, and sustainable communities after disasters: strategies, opportunities, and planning for recovery. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC). (2007). IASC guidelines on mental health and psychosocial support in emergency settings. Geneva: IASC.

Kronenberg, M. E., Hansel, T. C., Brennan, A. M., Osofsky, H. J., Osofsky, J. D., & Lawrason, B. (2010). Children of Katrina: Lessons Learned About Postdisaster Symptoms and Recovery Patterns. Child Development, 81(4), 1241-1259.

Kukihara, H., Yamawaki, N., Uchiyama, K., Arai, S., & Horikawa, E. (2014). Trauma, depression, and resilience of earthquake/tsunami/nuclear disaster survivors of Hirono, Fukushima, Japan. Psychiatry & Clinical Neurosciences, 68(7), 524-533.

Math, S. B., Nirmala, M. C., Moirangthem, S., & Kumar, N. C. (2015). Disaster Management: Mental Health Perspective. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 37(3), 261-271.

National Research Council. Disaster Resilience: A National Imperative. Washington, DC:

The National Academies Press, 2012.

National Research Council. Launching a National Conversation on Disaster Resilience in

America: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2013.

Neria, Y., Nandi, A., & Galea, S. (2008). Post-traumatic stress disorder following disasters: a systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 38(4), 467-480.

Norris, F. H., Friedman, M. J., Watson, P. J., Byrne, C. M., Diaz, E., & Kaniasty, K. (2002). 60,000 Disaster Victims Speak: Part I. An Empirical Review of the Empirical Literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry: Interpersonal & Biological Processes, 65(3), 207.

Norris, F. H., & Stevens, S. P. (2007). Community Resilience and the Principles of Mass Trauma Intervention. Psychiatry: Interpersonal & Biological Processes, 70(4), 320-328.

Norris, F. H., Tracy, M., & Galea, S. (2009). Looking for resilience: Understanding the longitudinal trajectories of responses to stress. Social Science & Medicine, 68(12), 2190-2198.

Paxson, C., Fussell, E., Rhodes, J., & Waters, M. (2012). Five years later: Recovery from post-traumatic stress and psychological distress among low-income mothers affected by Hurricane Katrina. Social Science & Medicine, 74(2), 150-157

Pfefferbaum, B., Flynn, B. W., Schonfeld, D., Brown, L. M., Jacobs, G. A., Dodgen, D., & ... Lindley, D. (2012). The integration of mental and behavioral health into disaster preparedness, response, and recovery. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 6(1), 60-66.

Phillips, B. D. (2009). Special needs populations. In Koenig, K. L, & Schultz, C. H. (Ed.), Koenig and Schultz's disaster medicine: comprehensive principles and practices (pp. 113-130). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Reifels, L., Bassilios, B., Forbes, D., Creamer, M., Wade, D., Coates, S., & ... Pirkis, J. (2013). A systematic approach to building the mental health response capacity of practitioners in a post-disaster context. Advances in Mental Health, 11(3), 246-256.

Reissman, D. B., Schreiber, M. D., Shultz, J. M., & Ursano, R. J. (2009). Disaster mental and behavioral health. In Koenig, K. L, & Schultz, C. H. (Ed.), Koenig and Schultz's disaster medicine: comprehensive principles and practices (pp. 103-112). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

SAMHSA. (2012). Trauma-Informed Care and Trauma Services. Substance Abuse and

Mental Health Service Administration. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

SAMHSA. (2015). Trauma-Informed Approach and Trauma-Specific Interventions. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration. Retrieved November 22, 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.samhsa.gov/nctic/trauma-interventions

Sangalang, C., & Vang, C. (2017). Intergenerational Trauma in Refugee Families: A Systematic Review. Journal of Immigrant & Minority Health, 19(3), 745-754.

Sapolsky, R. (2010). Stress and Your Body (pp.3-4). The Teaching Company

Schreiber, M. D., Yin, R., Omaish, M., & Broderick, J. E. (2014). Snapshot from Superstorm Sandy: American Red Cross mental health risk surveillance in lower New York State. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 64(1), 59-65.

Shultz, J. M., Espinel, Z., Galea, S., Hick, J. L., Shaw, J. A., & Miller, G. T. (2007). SURGE, SORT, SUPPORT: Disaster behavior health for health care professionals. DEEP Center: Panamericana Formas e Impresos S. A.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2015). Disaster technical assistance center supplemental research bulletin: Disaster behavioral health interventions inventory. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/dtac/supplemental-research-bulletin-may-2015-disaster-behavioral-health-interventions.pdf

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2017). Disaster Technical Assistance Center Supplemental Research Bulletin. Greater Impact: How Disasters Affect People of Low Socioeconomic Status. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/dtac/srb-low-ses_2.pdf

Sylwanowicz, L., Schreiber, M., Anderson, C., Gundran, C. D., Santamaria, E., & Lopez, J. F. (2017). Rapid Triage of Mental Health Risk in Emergency Medical Workers: Findings From Typhoon Haiyan. Disaster Medicine And Public Health Preparedness, 1-4

Thormar, S. B., Sijbrandij, M., Gersons, B. P., de Schoot, R., Juen, B., Karlsson, T., & ... Van de Schoot, R. (2016). PTSD Symptom Trajectories in Disaster Volunteers: The Role of Self-Efficacy, Social Acknowledgement, and Tasks Carried Out. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 29(1), 17-25.

Turner, F. J. (2011). Social work treatment: Interlocking theoretical approaches. 5th ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR). (2009). UNISDR terminology on disaster risk reduction. Retrieved from http://www.unisdr.org/files/7817_UNISDRTerminologyEnglish.pdf

van den Berg, B., Wong, A., van der Velden, p. G., Boshuizen, H. C., & Grievink, L. (2012). Disaster exposure as a risk factor for mental health problems, eighteen months, four and ten years post-disaster - a longitudinal study. BMC Psychiatry, 12(1), 147-159.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2013). Building back better: Sustainable mental health care after emergencies. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Yehuda, R., & Flory, J. D. (2007). Differentiating biological correlates of risk, PTSD, and resilience following trauma exposure. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(4), 435-447.